Turnback Maneuver

Master the engine failure after takeoff turnback with one of the most detailed courses on this subject.

Definition

The turnback maneuver after engine failure after takeoff consists of a procedure, where the pilot of a single-engine airplane who lost the engine shortly after takeoff, turns around and lands on the takeoff runway in opposite direction (choosing another runway or an airport grass area are alternatives). Synonyms for this maneuver are the turnaround maneuver, the impossible turn, the improbable turn, and the possible turn, all referring to the same.

A Viable Last-Resort Option

We would like to state upfront that this turnback maneuver is a last-resort maneuver only, and should only be considered to be flown if all of the following conditions are met:

- There are no suitable emergency landing sites lying straight ahead or in a reasonably narrow angle around your takeoff path.

- The pilot has sufficient altitude for the maneuver (this is an individual altitude, based on the airplane make and model, weight and environmental conditions, as well as pilot capabilities and proficiency – with insufficient altitude, the maneuver will fail, regardless of how well you fly).

- The pilot has been thoroughly trained in this maneuver in the specific airplane make and model (do not attempt this in a real emergency if you have never flown it before).

- The pilot is proficient at the maneuver by having practiced it reasonably recently (exact recency needs depend on the pilot).

- The pilot has briefed the maneuver explicitly before takeoff, including minimum turn around altitude converted to MSL and turnaround direction based on wind direction.

The FAA generally recommends in the case of an engine failure after takeoff to land straight ahead within a narrow angle of your takeoff path, without changing heading excessively. Turning back is discouraged, especially in the presence of viable straight-ahead options, due to the high stall/spin accident rates when the turnaround maneuver is flown incorrectly. This is precisely what we recommend as well at Academic Flight.

However, the FAA also states in Advisory Circular AC 61-83J, Section A.11.4: “Flight instructors should demonstrate and teach trainees when and how to make a safe 180-degree turnback to the field after an engine failure. Instructors should also train pilots of single-engine airplanes not to make an emergency 180-degree turnback to the field after a failure unless altitude, best glide requirements, and pilot skill allow for a safe return. […] During the before-takeoff check, the expected loss of altitude in a turnback, plus a sufficient safety factor, should be briefed and related to the altitude at which this maneuver can be conducted safely. In addition, the effect of existing winds on the preferred direction and the viability of a turnback should be considered as part of the briefing.” This is in line with our above recommendations and training.

Indeed, there are airports where the options lying ahead are simply not good, and in such a situation, if the pilot has sufficient altitude and the training and proficiency to execute this maneuver, it may be her/his best option (entirely at her/his own discretion, judgement, and risk). We do not encourage you to fly this maneuver. We merely give you the knowledge and training to do so with a reasonable chance of successful outcome if you choose to. Without the knowledge and training, attempting this maneuver is almost inevitably a disaster and has led to many stall/spin accidents.

It is to be noted that in glider training, rope breaks are practiced routinely with the blessing and encouragement of the FAA. Gliders have a much better glide ratio, of course, but the intelligent individual discovers that this merely results in a higher altitude requirement for single-engine aircraft, not the impossibility of the maneuver. The inconsistency in this discrepancy in training requirements between glider pilots and airplane pilots can be resolved by considering that rope breaks are far more frequent than engine failures. Engine failures are thus apparently considered to be too rare of an occurrence to be addressed by an explicit training requirement for airplane pilots.

However, this argument is dubious at best, given that most seasoned pilots know someone who had an engine failure, and that a certain part of the pilot population spends much of its time in the traffic pattern: CFIs. Especially if you are a CFI, you may want to consider learning this. The FAA has now rectified this instructional deficiency in CFIs by including the turnback maneuver in Flight Instructor Refresher Courses (FIRC) in Advisory Circular AC 61-83J.

At the same time, relatively few pilots know that at max gross weight, climbing out at best-rate-of-climb airspeed (VY), in many basic trainers a turnaround is not possible at any altitude, because the airplane is so underpowered that your climb-out angle is shallower than your power-off glide-back angle. So even 5000 ft AGL would not be enough to turn around to the airport after a straight-out departure. This is a knowledge gap that cannot be rationalized by any accident statistic or maneuver difficulty level.

Course Content

- Academics: Online course or 3 hours of in-person academic instruction.

- Flight Lab: 1 flight simulator (ATD) session, two 1-hour flights, 1 hour of preflight/postflight briefings (fulfilled by one of our independent partner instructors and flight schools).

Theory (during Online Course/Academic Part)

Detailed theory is necessary, not just for knowledge, but also because we want your brain to spend some time thinking about the details of the maneuver. Thorough consideration leads to superior performance. Important things we will discuss in the theoretical component of this course include:

Performance Calculations

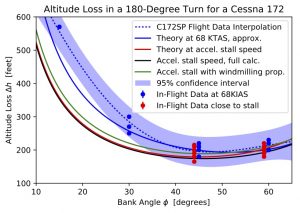

- Optimal bank angle and airspeed for turnaround (based on flight research papers by authors Jett and Rogers, we will derive the relevant equation with you)

- Impact of aircraft weight and atmospheric conditions on altitude loss during turn (unlike straight power-off glide distance, the altitude loss per degree of turn is airplane weight and air density dependent, as you will see from the above equation)

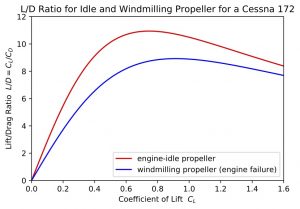

- Glide performance difference with engine idle (practice) vs propeller windmilling (real engine failure) (we will compute the difference between the two glide ratios using inferred aerodynamic data for the aircraft and published values from the POH).

- Maximum climb-out airspeed and a simple formula to determine it in flight

- The impact of wind on the maneuver (headwind and crosswind)

- First theoretical estimate of your minimum turnaround altitude based on aerodynamic airplane data and POH performance values (later to be refined in the airplane)

Above: Theoretical results will be compared to data measured in flight during this course.

Above: The drag difference between an engine-idle propeller during practice and a windmilling propeller with engine stopped in a real emergency must be taken into account. The plots have been calculated based on aerodynamic specifications published in McIver (2003) and the manufacturer’s Pilot’s Operating Handbook (for illustration only, do not rely on these approximate graphs in flight).

Procedures and Psychology

- Takeoff briefing

- Callouts during takeoff

- Division/merging of pilot attention between bank angle, airspeed, and outside world (simultaneous use of multiple sensory input channels)

- Open-loop vs closed-loop control inputs

- Psychological effects of stress in an emergency situation and proximity to the ground, and their impact on pilot control inputs

- Discuss and watch videos of common student errors (recorded of real students during training, like the one below)

Airmanship and Flying Qualities

- Airspeed management (speeds to fly, consequences of deviations)

- Flying angle of attack

- Airplane maneuvering stability (stick-fixed maneuver point vs stick-fixed neutral point, δe(n), dδe/dn(CG))

- Stall/spin characteristics of the airplane in skidding and slipping turns (many airplanes are fairly resistant to spin entries from slipping turns in a power-off configuration, but not from skidding turns)

- Proper direction of nose (left or right) in forward slip if one is needed to dissipate excessive altitude.

Sample Simulator Training Video

Below you can see a sample video from our turnback maneuver ground school, recorded in a Redbird FMX Advanced Aviation Training Device (AATD). The videos we will show you are actual recordings from prior (anonymous) students flying the turnback maneuver and illustrate common errors. In addition to observing recorded student errors, you will also have the opportunity to practice the turnback maneuver in the simulator yourself during the flight lab part of our course, before we fly in a real airplane (see below).

Practice (during Flight Lab)

In-airplane practice is a crucial component of this course. You cannot expect to execute this maneuver safely just after having thought about the theory. We highly recommend you get this training from an experienced pilot well trained in this maneuver (since this maneuver is not required for any pilot certificate, rating, or endorsement, according to 14 CFR 61.193 it is immaterial if this pilot is a CFI or not, in particular since this maneuver does not show up on the CFI FAA practical test, so many CFIs are unfamiliar and do not fly it). In the flight lab part of our course, you will learn:

In the Simulator (Aviation Training Device)

- Drill the sequence of control inputs and division of attention, until they become second nature.

- Explore common student errors (either your inadvertent own, or recreate the ones you saw in our videos).

- Study the impact of engine idle (practice) vs engine off (real emergency) on the maneuver (in the simulator we can pull the mixture to idle-cutoff).

- Experiment and crash the airplane as many times as you like.

- Develop an appreciation for how different Aviation Training Devices (ATD) feel from a real airplane, and how inaccurate their aerodynamic simulations are for crucial performance maneuvers (this is true in general, even for sophisticated-looking ATDs with motion like the Redbird FMX).

- Rehearse your upcoming in-airplane flights.

We recommend that you do all of the above already at home, after having taken our online course.

In the Airplane (at High Altitude)

- Power-off slow flight at 45- and 60-degree bank angles with the stall horn on.

- Full and imminent power-off stalls at 45-degree bank angles, with recovery from the stall while continuing the turn. The stall characteristics of some basic trainers in steep turns may surprise you.

- Evaluate the airplane’s susceptibility for departures into a spin from steep turns, by stalling it with a variety of rudder inputs.

- In-flight maximum climb-out airspeed verification based on airplane weight and atmospheric conditions.

- Practice a smooth, but quick transition from a power-off, nose-high, straight-and-level attitude to a 45-degree bank angle attitude close to stall speed, avoiding common errors.

- The importance of airspeed management (if you get too slow after the engine failure and hesitate, the turn becomes impossible to execute).

- Measure your altitude loss per 180 degrees of turn.

- Determine your approximate minimum turnaround altitude based on airplane make and model, weight, atmospheric conditions, and your pilot skills, by simulating the full maneuver at high altitude.

In the Airplane (at Realistic Altitude)

High-altitude practice alone does not do this maneuver justice. Therefore, after becoming proficient at the maneuver at high altitude, you will learn to fly it at realistic altitude, first taking off from a long runway and then, as a capstone exercise, from a short, 2200-foot runway. This is a crucially important part of the course, not only to get an accurate feel for the horizontal and vertical spacing during the maneuver for an actual landing, but also to experience the psychological effects due to the proximity of the ground. (Below we provide a recording illustrating such a training flight.)

This turnback maneuver can be executed reliably in a last-resort situation, but prior practice is imperative, and this practice must be as authentic as possible. Proficiency is also key, so refresh your learned skills often after the course.

Sample Flight Lab Video of Turnback Maneuver

The video below shows a (simulated) engine failure after takeoff in a Cessna 172P Skyhawk at 500 feet AGL from a 2200-foot-long runway. Full flaps and a forward slip were needed to get the airplane down onto the runway after the turnaround (with a real engine-out the altitude will be a bit less due to the windmilling propeller, see plot further above). The video shows the performance of a pilot who is well-trained in this turnback maneuver, but who has not flown it in the past six months and has never performed it at this particular airport before, in order to record a reasonably realistic situation. The performance is a little rough around the edges due to some lack of recency of experience, but the outcome of the maneuver is never in doubt, even at an airport with such a short runway.

References

There are several excellent references for the engine failure after takeoff turnback maneuver. They range from pioneering theoretical studies by NASA astronaut Brent Jett and his advisor David Rogers at the United States Naval Academy to practical in-flight videos by Sunrise Aviation’s CEO Michael Church.

- Brent W. Jett (1982), “The Feasibility of Turnback from a Low Altitude Engine Failure During the Takeoff Climb-out Phase”, AIAA Paper 82-0406, presented at the 20th Aerospace Sciences Meeting, 11-14 January 1982, Orlando, FL.

- David F. Rogers (1995),“The Possible ‘Impossible’ Turn”, AIAA Journal of Aircraft, Vol. 32, pp. 392-397.

- David F. Rogers (2012), “The Penalties of non-optimal Turnback Maneuvers”, Journal of Aircraft, Vol. 49, No. 1, pp. 257-261.

- Michael Church (2012), “Turn-Arounds – Managing Low Altitude Emergencies”, Sunrise Aviation, talk slides (http://www.sunriseaviation.com/turn-arounds.html).

- Michael Church and Ty Frisby (2012), “Emergency Turn-Arounds”, Sunrise Aviation, video (https://vimeo.com/34712443).

- Les Glatt, “Single-Engine Failure After Takeoff: Anatomy of a Turn-back Maneuver”, Presentation Slides, Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4 (http://www.safepilots.org/library/contributed/Anatomy_of_a_Turnback_Maneuver_Part1.pptx and analogous links for Parts 2-4).

- Evan Reed (2008), “Dealing with engine failure on departure and the ‘impossible turn”’, Flying Particles Club talk slides, Livermore, CA.

- “The Improbable Turn,” SAFE Broadcast with Russ Still, David St. George, and Rod Machado, Gold Seal Flight Training, February 8, 2018

(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4ackVNFct4I).

It is also important to consider though when the maneuver goes wrong. The following references include textual reports as well as videos of accidents:

- Mike Danko (2011), “The ‘Impossible Turn’ and Three Mooney Crashes in Two Weeks”, Aviation Law Monitor, with an included video of a fatal Mooney crash.